This post is off-topic, but can be important in all walks of life! To help out my friends with something I struggled with in the past, here is a post on understanding and beating procrastination. Although there are also study techniques, you can read the main points as guidance for dealing with any task.

First of all, almost all the information here is from an excellent free online course, “Learning to Learn” on Coursera, by the wonderful Dr. Barbara Oakley. This post aims to condense and summarise the utilitarian points.

This post is long, in the region of 5000+ words. Read a chapter a day or whenever you have time, so you break down into small, manageable chunks.

Learning to Learn

Focused vs Diffuse learning

Pomodoro (tomato) technique – study for 25 minutes (focused thinking), then reward yourself for 5 minutes, allowing your mind to enter diffuse thinking. You can also use 50 min/10 min, and a large break every 2 hours (e.g. 30 mins on top).

The idea is to put your undivided attention into studying, blocking out all external stimuli (distractions, like smartphones) and pour your brain out into books. Then, once a set period of time is up, it’s time to cut loose, and reward yourself for completing the task (a walk, play a quick videogame). Getting away from your desk for a moment allows your brain to enter diffuse thinking (day dreaming is totally fine!), which allows your brain to link what you have just studied with other stored concepts in your mind. In fact, this is a trick used by current and past braniacs, where after thinking profusely, they take a nap on a chair, and with an object in their hands that falls when they enter sleep, jolting them awake, they immediately write down what they were thinking. This is because in diffuse mode of thinking, their brain comes up with concepts that link what they’ve just learnt. I’ve reiterated this point twice, because not studying is not wasted time. Your brain is constantly learning (by forming connections between neurons), and condensing what it has learnt, even when you sleep (which is arguable as important as studying, and should be done for however long you feel the need to – some people feel refreshed after 7 hours, while others need 10 hours, or their mind won’t be alert for the day).

Use the pomodoro technique to get you in the practise. This allows you to not overthink your studying, and actually jump into the task at hand. Too often, we procrastinate because we think we need to plan further. Truth is, you can go back to the planning stage at anytime as part of your review process, but you won’t know what to amend if you don’t put your initial thoughts into practice!

Practice makes permanent – practice in small chunks everyday. The goal is to strengthen memories by living them over and over again, think like riding a bike: at first you have to learn to coordinate how every limb moves in unison, but with each day of practice, you get better and better, until you can instinctively ride a bike without overthinking. Or, even simpler: you can do basic addition, such as 2+2, without having to count with your fingers, because you’ve had a lifetime of practice. However, you don’t need a lifetime, so long as you practice often, ideally spread out over small chunks everyday (spaced repetition).

If you cram, such as in an all-nighter, or in the lead up to an exam, you don’t allow the ‘cement to settle’ in your brain, and instead start building your house on top of this wet ‘cement’, so your house will come tumbling down soon enough. By building the house over a longer period of time, instead of all in one day or week, you build a stronger foundation, which you can build on more easily. Think of how we start with 2+2 before moving on to the idea of linking this to multiplication, and then to complex equations. We need to get some practice in with the basics before we advance to the more challenging topics, and allow those concepts to solidify in our brains.

Chunking

It’s important to understand and gain context with the information you learn, rather than just rote memorisation. One way to do so is to link what you learn under chunks, which are pieces of information bound together by meaning or use. Imagine it’s like a (zip) folder on your computer, containing individual files that are related to each other. A chunk is a network of neurons used to firing together. Small chunked information can form larger chunks, as our brains takes mental leaps, and unites scattered pieces of information to form meaning. This enables us to master material and create interpretations (e.g. going from basic ice moves -> advanced moves -> a creative dance routine).

To form a chunk, you have to have a sense of the pattern you wish to learn (and form), as in the above example. While forming chunks, there is a heavy mental load, which can mentally exhaust you (as willpower is a finite source), but overtime, as you form chunks, this impact will lessen, and you’ll be able to recall information in an instant. The more you practise, the more ingrained these chunks become, so you don’t have to think about them consciously (like, how to walk). In academic practice, learning the connections between steps to a solution or problem is key (such as why we solve a maths problem in a certain order).

Chunk formation:

1) Focus your undivided attention on the information you want to chunk. Your working memory can only focus on around four ‘chunks’ of information at a time. When learning something new, all your working memory is involved, and your brain takes up all these available chunks to form new connections, but distractions will take up some (or all) of that space if you let them, thus reducing your learning ability. Overtime, concepts will only take up one space in your limited four slot working memory (e.g. if you drive a car, it will become second habit, allowing you to zone out, or focus on other things better – like the road).

2) Understand the basic idea you’re trying to chunk. Test yourself to see if you understand; explain it to someone else. Don’t assume you understand when you’re being taught by a tutor and you think ‘eureka’. You need to superglue disjointed pieces of information together to get the big picture. Comprehension of main ideas, or expertise, is understanding and applying knowledge, in a show of TRUE mastery.

3) Gain context: how, and when, to use this chunk. Context is going beyond the initial problem, and seeing more broadly (the big picture). Practising repeatedly, with related and unrelated problems (so you can see when to, and when not to, use the chunk), to see how your chunk fits into the bigger picture. Seeing the bigger picture first allows you to identify where to put the chunks you are constructing. Think of it as seeing the jigsaw art on the box, and how the pieces should fit, then actually performing the task of finding, and fitting those pieces together. Learn the major concepts first, then fill in the details.

To increase expertise, people increase the number of chunks they store, to allow for greater creativity. A chunk is a way of compressing information compactly, and as you gain expertise in a field, those chunks become bigger, and more strongly ingrained in your brain. A collection of chunked concepts is called a ‘library of chunks’, where you can easily find solutions to a problem by using your diffuse thinking as a ‘catalogue’ to find the appropriate chunk to help you. Traditionally, we’d use focused thinking only, to solve questions in a sequential/liner fashion, but creative diffuse thinking allows us to link different concepts together. This combination allows us to tackle objects that are familiar, but new, such as applying physics questions to real-life examples.

Chunks help us understand new concepts by relating them together, for example, if you know a foreign language, it becomes easier to learn a programming language as there is an order and syntax to both.

Mastering a new subject means learning the basic chunks, also how to select and use different chunks. Best way to practice this is to jump back and forth through different situations/problems that require different approaches, techniques and/or strategy to solve. This is called interleaving. Once you have the basic idea down, start interleaving your practice with different types of problems, approaches, concepts, or procedures (example, learning concepts in one chapter which you can apply in another). This builds flexibility in your learning, allowing you to think more independently.

Illusions of Competence

Illusions of competence is thinking you understand the material, such as:

– Reading, or re-reading material, is not as effective as active recall. Active learning trumps passive learning.

– Just looking at the solution, but not performing any act, does not build the underlying circuitry between neurons.

– Highlighting and underlining has to be done carefully; overuse these methods, and you’ll fool yourself into thinking you’ve learnt the material.

To beat the illusions of competence, you need to test yourself to see if you understood the concepts. Test yourself through active recall, where you close a book, and write down as much as you can remember, and then go back to see where there are gaps in your memory. Practise exam papers or questions, and learning from mistakes, becomes highly valuable.

Test yourself in multiple physical environments to reduce subliminal associations, so you become independent of your environmental cues and do not get thrown off from performing when you are forced to take an exam in an unfamiliar setting. Learning to study in your bedroom, a library, a cafeteria, on public transport, etc. will make it easier to recall information in any situation. On the other hand, there is also research that indicates the more closely you match the exam conditions, the better your exam grades will be as you will become used to the exact conditions of the test hall. A clean desk, no noise, and a timed condition may help you.

Overlearning is continuing to practice what you have mastered. It can be useful for automaticity (automatic response or habit), such as a tennis forehand, ice skating move, or public speaking. However, repetitive learning in a single session can be a waste of valuable learning time, as it doesn’t strengthen long-term memory or develop skills effectively. Spaced repetition, on other other hand, is a valuable practice in deepening chunked values and understanding. [Beware of repeating mastered concepts; they are far too easy, and a massive waste of time, but also is an illusion of competence. Examples would be practicing 2+2, rather than more complex additions].

You want to focus your studies on what you find difficult. This is deliberate practice.

Einstellung is a type of mindset, where there is a roadblock in thinking. Your initial idea may prevent a better solution being found. You need to unlearn older, erroneous ideas to learn new ones. It can stop you trying out new techniques and ways of thinking, which may cause a block in creativity.

- An example is a learned bad habit. You may have practiced a pattern a certain way for years, but you’re going to have to bite the bullet, and re-learn the better or correct way.

- Another example is you come up with a solution to a problem, and you immediately run with that first idea, but if you take your time and plan for longer, you may come with an even better method].

“Jumping into the water before you learn to swim is a recipe for sinking.” Blindly working on a new concept is going blindly into the darkness. Planning and understanding how to obtain the solution is important, even more so than the answer.

Procrastination

Procrastination is the pain associated with tasks. You instead turn your attention to something more pleasant, which releases dopamine (a neurotransmitting chemical in the brain that makes you happy), but this is temporary, and with enough repetition, turns into a bad habit, and you become accustomed to the ‘reward’, so the happiness becomes hollow over time. However, once you begin the ‘dreaded‘ task, it doesn’t seem so bad. Remember, you can use the pomodoro technique to help you start.

A bad habit results the temporary release of dopamine, in which you fool yourself with stories or excuses due to the pain associated with studying, which makes your brain seek pleasure (release of said dopamine). Over time, you build up a dopamine resistance, this means you need even more stimuli to feel the ‘high’ of the ‘drug’ because you aren’t satisfied with the previous amount of dopamine since its losing its’ effectiveness on you. [An example would be, you play a new video game for one hour one day, and you feel excited. However, the following day you don’t feel as excited with just one hour of play, so you end up playing for longer, and longer each day, until you are playing the game for hours on end because you’ve become addicted, or formed a bad habit]. There is microscopic damage that accumulates in your brain over time, so even if you don’t feel the effects of procrastination in the early stages, you will soon, and then, your foray into a seemingly throwaway activity won’t seem so innocent.

However, if you treat an activity that you’d procrastinate on as a reward FOR doing something productive, you can actually rewire your brain into forming a GOOD habit. At first, performing a task for the first time seems challenging, but this is because your brain is inundated with stimuli – your brain, in other words, is on hyper-alert! Over time, you will become more adept at the task as your brain switches itself on auto-pilot since it is no longer overburdened with stimuli, only some of what goes on in your environment will register. [When driving a car for the first time, you need to be aware of how to control the gear stick, pedals, speed, awareness of road users, traffic lights, pedestrians, etc. Once you have the hang of it, driving becomes sub-conscious, and you instead focus on the road users and pedestrians, as these are the factors most likely to be in flux.] Tasks also become less daunting with chunking, as you break down large tasks into more manageable compartments for easier learning.

Habits make for no bargaining with one’s self

How to form a (good) habit

A habit is an energy saviour (your brain is on auto-pilot, allowing you to concentrate more on the stimuli that changes, or in studying, allows you to concentrate on the new material to learn, rather than having to fight your brain into studying and against distractions). Habits can be good, neutral, or bad. A habit can take months to develop, or can occur instantaneously (if you touch a hot pan, you quickly take your hand away, thus you’ll learn forever have this habit ingrained in your mind; however, changing your exercise and diet lifestyle can take consistent effort over months before you don’t get the urge to go back to your old habits).

There are four parts to forming a habit:

- the CUE – this is the trigger that whisks you away into frenzied action. It could be location (you walk by a restaurant), time (it’s late at night, you feel urged to do your homework), how you feel (you feel sad, so you may look for ice cream or TV), reactions (you accidentally touch a hot object, so you flinch – this ‘action’ is the routine), you hear a sound (notification from your phone). Distractions are cues, and can be the source of time wasting (e.g. you’re bored, so you decide to surf the web aimlessly).

- the ROUTINE – following the cue, there is action.

- the REWARD – for following a certain action, there is a reward that helps you associate a cue with a routine/action. You release dopamine after completing an action, which tells your brain that you should do more of this, because that felt good! Thus, if you feel angry, and you decide to go for a run, your brain will slowly associate being angry with going for a run, helping you to more easily go for a run each time you’re angry, rather than something more destructive like punching a wall. This then enables you to go on auto-pilot, and think about what made you angry in the first place, and how you could avoid that in the future.

- the BELIEF – habits have power because of our belief in them. If you believe you can’t study until the sun goes down, then you’re doomed to keep repeating your actions/bad habits.

Procrastination is an easy mistake for anyone to get into. This is because rewards are readily available, so it’s much easier to get into a bad habit. If you are presented with a choice between watching a film or doing school work, you’ll receive the reward much more quickly if you watch a film rather since completing school work may take longer to see the reward from. This is where the opportunity presents itself. We don’t reward ourselves as readily as we are rewarded from doing something easy. Being productive is hard, and so really, we should be giving ourselves and even BIGGER reward. This is key. If we don’t have a proportionally greater reward for a more challenging task, then our brain will think “What’s the point? I can get the same reward for doing something easier.”

You can combine this notion with rewiring your brain to doing more difficult or unpleasant tasks. Reward yourself more frequently when you start a new habit. For each paragraph of an essay you write, give yourself a small break where you read your text messages, or surf the internet. Start small; e.g. ease into a diet: replace your fizzy drink with juice, then another day, replace it with water, then slowly over a few days or weeks, start replacing your breakfast for something healthier, then your lunch too, and then your entire day. Reward yourself MORE for bigger/challenging tasks. If you write one page of your new book, give yourself a one-half hour TV show to watch. If you complete a whole chapter, allow yourself a two-hour film to view.

Habits: Part Deux

So we know that we need to change our reward structure to form a good habit, but how do we actually start to replace our bad habits? You need to change your reaction to a cue. This will take WILLPOWER. You have a limited amount of willpower, which is the conscious effort you can give to an activity every day. It is a valuable resource, so use it wisely. [You walk into a supermarket and see chocolate (cue). Instead of putting the chocolate in your basket (routine), you are going to change direction and walk to the fruit aisle (new routine). As a reward, allow yourself the fruit at home (reward), or buy a new song (reward), or something similar, so long as you’re not just replacing one bad habit with another – e.g. packet of crisps]. As an aside, this blog post took me a few days to write, and every couple paragraphs, I’d listen to music to reward myself for the effort. It’s okay to space out your action like I did, eventually, I was spending more time writing with each day.

To motivate yourself, you need to trick yourself. Tell yourself to ‘get on with it, and stop wasting time’ when faced with something you don’t want to do. You can also re-frame an unpleasant task, such as tidying up the house to see how fast you can complete it, or how you’ll get an extra bit of exercise in.

Focus on the process, not the product. If you have homework with five questions, focus on the actions needed to complete it, such as chunking and understanding the coursework. If you focus on the product itself (“I need to complete these five questions”), you don’t know how long those five questions might take, and instead may frustrate yourself, and you may quit. This is the pain association that I wrote about, because you find it painful to carry on since you focused on the end result (the product), and would rather do a more pleasurable activity. If instead you focused on the learning aspect, you’ll find eventually you’ll complete the task with less pain since even if what you’re learning does not interest you, you’d have worked on your skills to chunk and develop your technique. [Another example is practicing drills for football will help you perform better during a match, which you are more interested in].

This is another reason why the pomodoro technique is useful. The method helps you focus on the process (the passage of time, the flow of doing a task), not the end result. You don’t focus on how far away from the end you are, rather you KNOW you have a set period of learning time, so you relax into the flow/process by removing an extra stimuli from your mind.

You may find yourself wanting to go back to the old habits. If you do relapse, that’s okay, don’t belittle yourself, just pick yourself back up, and continue (you’re not starting again, you’ve already made a start and put the effort in to do so). Having belief in your new habit is encouraged to get through the bumps. A support network of friends with positive reinforcement or accountability may also be beneficial. [Don’t tell your friends what you plan to do, such as telling them as part of your New Year’s resolution, you plan to lose weight. Your friends will likely smile and cheer for you, but this will release dopamine which may trick your mind into thinking you’ve already lose some weight. Instead, don’t tell them, and get exercising as soon as you can. If you reach a testing period where your mind waivers, you can go to them for support, and mention your current progress, for which they will congratulate you on, and thus trick your brain into working out further, as your friends’ compliments made you feel good, and when you feel good, your brain feels good].

A good way to keep perspective of the big picture (what you’re trying to accomplish), is to make a weekly and daily to-do list. Keep it very brief (around six tasks), and mix up the difficulty (some are to start your tax return, another is to cook). Work on the most difficult tasks first, and interleave your day with easy tasks in between and reward sessions. Give yourself a time deadline, which may seem counter-intuitive, but will bring haste/urgency to the tasks so you don’t procrastinate it until the evening.

Sleep & Exercise are important, too

As we briefly touched upon earlier, sleep is also a vital part to learning. When you are awake, you build up metabolic toxins in your brain (yes, toxins are a teal thing), which can interfere with thinking. The act of sleeping ‘washes’ away these toxins, leaving you in a better state for thinking. Hence, it is important to always get a good-night’s sleep before an exam, or even in general. Sleep also has the added benefit of memory defragmentation, where you keep the memories your mind deems important, and gets rid of the memories that aren’t (think of how you can hardly remember what strangers’ faces look like). This also means ‘if you don’t use it, you lose it’; if you only practise ‘trigonometry’ only once, you will forget almost all of it. In fact, you forget most of what you learn in a day, which is why it’s important to employ spaced repetition, so it stays in your mind for longer. However, even a learned concept will be forgotten in time, if not practised, such as forgetting a language you used to be fluent in.

There is also some research that indicates studying before bed, or at least thinking about what you’ve learnt, increases the likelihood of dreams regarding the topic, which in turn helps to consolidate these memories.

Exercise is also important as it can create new neurons and neural connections, especially if done before studying, as increasing your heartbeat for even 10 minutes aids in better learning for a short period of time. According to one study, it’s cardio, not weight lifting, or high-intensity interval training, that seemed to create new neurons.

Memory

My favourite section, because this is the part with the most variance, and the part which you can pick and choose from. This section will give you pointers on how to actually commit new concepts to memory. When we learn, we consolidate (store) short-term memory into long-term memory. Reconsolidation occurs when we recall a memory, and our memory is changed as a result (this is why people’s recollections of events is not considered strong proof in courts, because every time we recall an event, the memory actually changes in our minds, as we forget some details, strengthen others, and sometimes completely warp the idea and remember something that didn’t actually happen). Reconsolidation also transpires during sleep, this helps you to strengthen those memories, and why spacing out your studies over a longer period helps with learning.

The greatest tactic for memory are mnemonics. There are a few types of mnemonics, and I’d urge you to do more research to find which ones may suit you most, as your individual learning style and the topic you wish to master will influence which mnemonics work best for you. [Use this resource to help].

- Music (lyrics, like the ‘ABC’ song)

- Name (1st letter of each word, like ROY G BIV for colours of the spectrum: Red-Orange-Yellow-Green-Blue-Indigo-Violet)

- Expression/Word (e.g. PEMDAS/operations for maths: Please excuse my dear aunt Sally)

- Model (constructed visual aid, like the food pyramid)

- Rhyme

- Note organisation/notecard/FLASHCARD/Cornell System (very effective recall technique)

- Image (constructed visual aid which triggers you to recall)

- Connection (connection information already known, e.g. LONGitude is the the long line that runs North and South).

- Spelling (e.g. the principal at school is your pal, but a principle is a rule).

There is one dangerous secret that is the key to all those memory champions that can recite the digits of pi to thousands of numbers, and that is a skill that initially takes some time to develop, but is your best memory tool at disposal. This particular method is called the MEMORY PALACE. I’ll leave you to do some research on that if you’re interested. Start small, and you’ll get the hang of it.

The Student becomes the Master

Be flexible in your learning. Try out new techniques and find which ones work for you, and be ready to change your mind, as well as admit errors so that you can learn from mistakes. Sometimes we develop bad habits, and stick to them because of the invested cost, even though what you were doing may have been inefficient or incorrect, and it may be a struggle, but do seek to change your behaviour if it is deemed best to do so.

Persevere in developing good habits. You are responsible for your own learning, don’t rely on a linear structure, uncover a broader perspective of the material to broaden your understanding (in physics, I’d always question how something was applicable in the real world). Tune out critics, they’re jealous or envious as a result of our society which makes life seem all about success. I’ve also seen people who wanted to save face when they’ve made a mistake or are lagging behind in their studies; take humility, because what matters at the end is if you have learnt the material well, not what others may think of you or the grade on your paper. Don’t fall into the imposter syndrome of thinking you don’t deserve to be at the university or workplace you’re at because you think everyone else is more intelligent than you. Many people think they’ve cheated their way into those establishments because how could you have gotten there if there are people who are ‘more talented’? Because you are also that talented, don’t fool yourself into thinking otherwise.

Let’s say you read through a textbook, then answer any questions, then read the solutions. This is somewhat passive, so instead after reading a chapter, use active recall to see what you can remember, do practice questions, but also be able to set your own questions up. Remember to skip sections you’ve already mastered, otherwise you’re just wasting valuable learning time. Group sessions may be beneficial to discuss topics.

Explore beyond the curriculum, use plenty of resources to give yourself a rounded view. Being inquisitive and asking questions (there are no dumb questions!) helps to overcome your fear. Being able to think independently is a great skill.

Perhaps the best thing you can do is TEACH!

Teaching is one of the best methods of memorisation because you have to be able to:

- Clearly explain a concept as if you’re teaching someone who is a complete beginner

- You’re not trying to be impressive with your vocabulary, but able to be understood by someone who does not study in your field

- It allows you to see if you are able comfortable and flexible with what you know

- Also, to see if there are gaps in your knowledge because you may have forgotten some things, and cannot explain other concepts well enough

- You may raise further questions of your own or from the person you’re teaching, allowing you to explore the subject even further

If you don’t have somebody to teach to, no problem; programmers often use a ‘rubber duck’ toy, or any other inanimate object to go step-by-step from the start to find errors in their coding because they have to explain what each line of code does. You can also talk to a mirror, record yourself, write a blog post (hint-hint), make a video, tutor, or teach a classroom!

Exam Practice

When preparing to study for an exam, make sure to do a lot of practice papers/questions, specifically doing more work on those types of questions with which you struggle the most. Did you understand the questions and answers, ask for help if you didn’t? You wouldn’t want to live in a house if you’ve build it on shaky foundations, would you?

Get a good night’s sleep for the exam, if you’ve been practicing over the entire year in small chunks (spaced repetition), you won’t need to cram, and you’ll actually have a solid foundation (also allows you to save your energy for the day of the exam). Furthermore, the more varied your testing environment is (studying in different rooms of the house, library, park, etc.) allows to you to be comfortable accessing your memories anywhere. Taking exams in test conditions is also vital (match as closely as you can what the real exam would be like: typically, this is quiet room, no distractions allowed on the desk, timed condition).

When the exam arrives:

- Scan the paper briefly, to get a sense of the questions/problems.

- DO the most difficult problem first, then switch to an easy problem, especially if you get stuck while doing the hard question. This allows your brain to shift from focused to diffuse mode while you’re answering the easy question, allowing you to think about how you could approach the hard question. Sometimes, I get ideas on what to do after I’ve left it for a while, rather than waste my limited time throwing a bunch of methods at the question.

- This also means you can make progress on the difficult questions, rather than leave them blank, or not have enough time to answer all the challenging questions to some degree.

- Remember, pull yourself away from a problem when you can’t write about it any further. Let your mind dwell and ponder, while you are taking it easy on a less strenuous problem.

- Stress is bad, shift your thinking from “This taste has made me afraid” to “This test has got me excited to do my best”, and indeed that’s the way it should work. Take deep breaths to help you relax. Standing like a superhero for 2 minutes before you walk into the exam room may work for you (it’s a concept of “fake it till you make it”).

- Cover up multiple choice answers, and instead try to recall your knowledge.

Closing Words

Lastly, make sure you receive help with learning difficulties and your mental health.

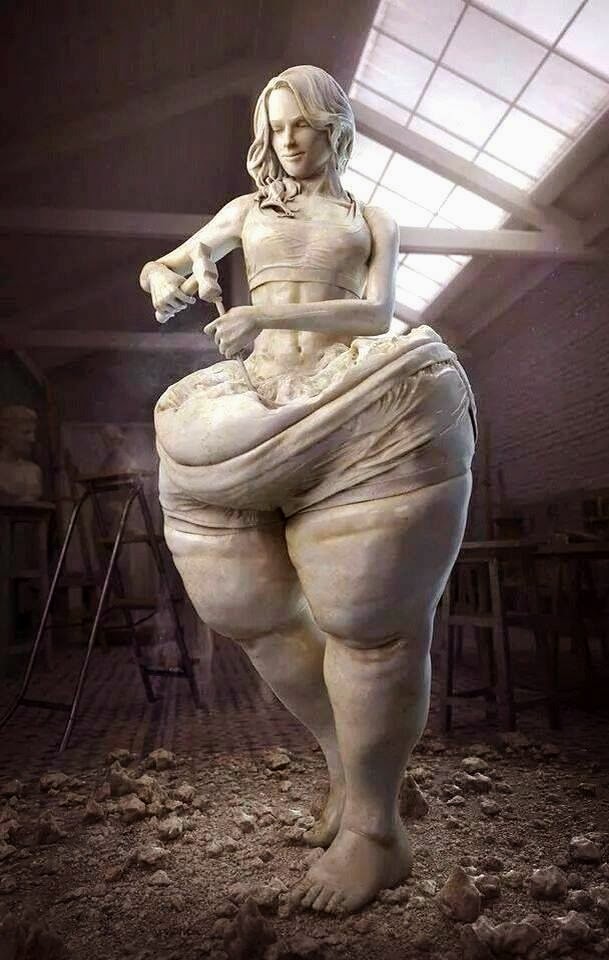

I like this picture to illustrate a point. Bad habits can help with depression by relieving you of the symptoms. However, those side posts that hold your mental health up are unstable, and will one day crumble, and you will face the full weight of your issues. The looming threat isn’t great for your psyche, either. You’ll also experience pain periodically due to crumbling pieces. Thus, it is a good idea to use better supports, which may be harder to establish and maintain, but are stronger. You may eventually build an entire stable foundation, eliminating the issue almost entirely (where applicable).

[PLEASE, if you do have depression, anxiety, chronic stress, learning difficulties, disabilities, etc. PLEASE, PLEASE, talk to someone. Ideally, a medical professional with whom you can work with. If they’re not great, ditch them, and find someone else. If that seems too scary, remember it’s all confidential, or you can talk to your best friend or relative].

Another good analogy is chipping away at a rock to build a statue. It may take small, seemingly insignificant chipping away at it, but eventually you’ll have something of beauty. You sculpt yourself. It will take time, but the sooner you start, the better, and every little helps towards the end goal.